Where to Draw a Line on Climate Denial

More Questions than Answers

More Questions than Answers

It appears that presidential press secretaries are not the only ones doing headers into the hedges to avoid having to answer potentially embarrassing questions. Sean Spicer’s dive into the history books made for great journalistic sport and allowed Melissa McCarthy to show-OFF her considerable comedic talents.

Spicer’s hiding in the greenery is not exactly what’s implied by the term hedging. However, as I will explain a bit further on, companies and organizations like Google, Shell, Bank of America, the US Chamber of Commerce, and Amazon are doing their own version of the Spicey — a hedging maneuver they would have preferred to remain hidden from journalists and the climate defense community. Maneuvers the climate community should wish them not to engage in in the first place.

Investors understand hedging to be a strategy designed to offset a potential loss on one investment by purchasing a second investment that is expected to perform in the opposite way. Most of us engage in the practice whether we’re aware of it or not. The purchase of health or auto insurance, for example, is a form of hedging.

Hedging in politics is not very different from pairing investments or paying for insurance. The goal in each of the cases is to offset a potential loss through a countervailing action. In politics, the loss usually being hedged against is access rather than dollars.

Political hedges come in a variety of forms and flavors. For example, a political action committee (PAC) that contributes campaign dollars to candidates of both parties is hedging its bets the same as any gambler.

Another hedging example is when a contributor sponsors activities of organizations with opposing stances on climate science, e.g., the Center for American Progress (CAP) and the American Conservative Union (ACU). The giver in these cases is looking to establish a line of credit with each of the groups, credit lines that could be drawn down in the future for help in passing legislation, or an introduction to an influential lawmaker or cabinet secretary.

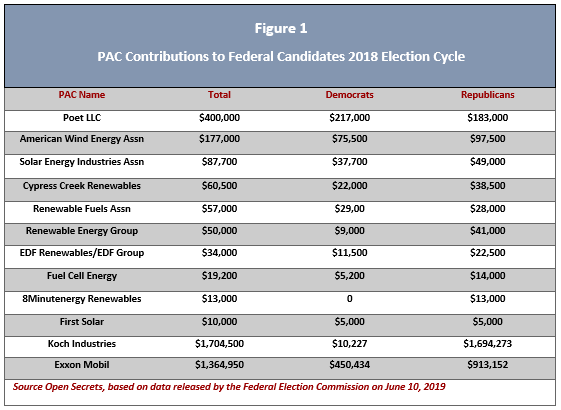

Increasingly solar, biofuel, and wind companies are making hedged investments through their PACs. The biggest renewable-related PAC in the current election cycle, according to Open Secrets is Poet LLC, an ethanol company. (See Figure 1)

The totals in the renewable energy PACs are small compared to Koch Industries or ExxonMobil; however, size doesn’t always matter — at least in the case of political contributions. For new companies and emerging industries, contributions of any size are noticed. Moreover, support is not always measured in hard cash. Soft contributions, like a willingness to knock on doors, arrange meet-and-greets, or link websites, are also political currency.

Savvy politicians understand the meaning of the phrase to each according to their abilities. They look upon donations of time and money as earnest money.

In the case of campaign contributions to lawmakers, the hoped-for result is an open door that offers the opportunity to seek the assistance and support of the successful candidate on a variety of issues — some as commonplace as an invitation to give the keynote speech at an annual conference in their district or controversial as a carbon tax.

Readers should note that no part of this discussion is meant to suggest members of Congress are for sale or charge entrance fees before they meet with anyone. Love it or hate it, the reality of running for office is that campaigns cost money. There’s much wrong with the electoral system as it’s practiced now, but that’s a topic for another day.

Hedging political contributions — in principle — is no more evil or good than buying health or auto insurance or reducing the risk of an investment with another investment. There are times, however, when choices between conflicting investments need to be made for ethical reasons rather than political expedience, i.e., it’ just the right thing to do.

When ethical questions are avoided, politics takes on the mantle of a Donald J. Trump — a cloak of distracting colors intended to cover-up ethical lapses or turn attentions elsewhere.

Google has been much in the news lately because of its financial support for climate denialist organizations. Google and other companies are now being targeted by climate defenders demanding the companies close the money tap to climate deniers. There is no such thing as an anodyne grant of money to these organizations — it all enables them to obstruct the nation’s transition to a low-carbon economy.

In mid-October — Mothers of infants held a “nurse-in” outside Google’s offices in King’s Cross, UK. Members of XR Youth (Extinction Rebellion) climbed on top of the entrance to Google-owned YouTube, holding a banner that read “YouTube, stop climate denial.”

Before the nurse-in, a Guardian investigation revealed that Google had made “substantial” contributions to some of the most notorious climate deniers in Washington despite its insistence that it supports political action on the climate crisis. (emphasis added)

In her article on the investigation, Stephanie Kirchagessner singles out Google for its support of more than a dozen organisations that have campaigned against climate legislation questioned the need for action or actively sought to roll back Obama-era environmental protections. From the list of recipients Kirchgaessner focuses on the Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI), a leader in the climate denier community.

In CEI’s own words:

CEI questions global warming alarmism, makes the case for access to affordable energy, and opposes energy-rationing policies, including the Paris Climate Treaty, Kyoto Protocol, cap-and-trade legislation, and EPA regulation of greenhouse gas emissions. (Emphasis added)

Translate the CEI paragraph into plain English, and the paragraph would read:

CEI denies the science of global warming, supports the continued use coal and gas both in the US and overseas, opposes the UN treaties committing the nation to combatting climate change, or in any way limiting or penalizing the use of fuels known to be the source of the greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change — including by regulation.

Myron Ebell, director of CEI’s Center for Energy and Environment, was intimately involved with the Trump transition teams for the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Department of Energy (DOE). Ebell, along with Stephen K. Bannon, Scott Pruitt, and Stephen Miller, advocated for pulling the US out of the Paris Climate Accord (Accord). Against the advice of then-Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, then-Secretary of Defense General Mattis, and others, Trump announced his intention to start the process of pulling the US out of the Accord in June 2017.

Far worse than Ebell advocating the cancellation of the US involvement in the Accord were the recent — albeit unsuccessful — efforts of CEI to have EPA issue a retraction of the 2009 endangerment finding.

The finding, along with the case of Massachusetts v. EPA, confirms EPA’s legal obligation to regulate CO2 and other greenhouse gases and formed the foun-dation for President Obama’s Clean Power Plan (CPP). Both will be heavily relied upon by the courts in deciding the mounting number of legal challen-ges to Trump administration efforts at weakening the nation’s environmental framework by the rescission or substantial revision of regulations issued pursuant to climate-related legislation like the Clean Air and Water Acts, and the National Environmental Policy Act.

Other prominent climate denier organizations gifted with Google funds are the Heritage Foundation and its lobbying and political arm Heritage Action. The Foundation and Heritage Action speak of solar and wind as if they were mildly interesting untested curiosities rather than the two biggest sources of new electric generation in the US.

Heritage Action walks the halls of Congress passing along the lies of the Foundation and other denier groups, e.g., the Texas Public Policy Foundation (TPPF) and the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC). TPPF, like the State Policy Network (SPN) supported by Google, is encouraging the public to sign a “climate pledge” that falsely states “our natural environment is getting better” and “there is no climate crisis.”

Google has not let the reporting of the Guardian and the Mothers of Infants’s nurse-in go unanswered:

We’ve been extremely clear that Google’s sponsorship doesn’t mean that we endorse that organisation’s entire agenda — we may disagree strongly on some issues.

Our position on climate change is similarly clear. Since 2007, we have operated as a carbon-neutral company, and for the second year in a row, we reached 100% renewable energy for our global operations.

Google defends itself by saying they are as just one of many companies that contribute to organisations while strongly disagreeing with them on climate policy. It’s an argument I’ve used on many occasions — only to face the question, “if they jumped off the roof, would you do the same?” No, mother I wouldn’t.

Google has a point. It is hardly unusual to find an organization contributing to other groups with which they have very little in common, hoping to trade their cash or other currency for the group’s support on issues they might agree on, e.g., opposition to tariffs on foreign steel. However, my mother and those who held a nurse-in are also right. Just because others do it doesn’t mean you’re right to do “it.”

Google is certainly not alone in playing both sides. Oil and gas companies spend millions of dollars on campaigns to fight climate regulations at the same time as touting their dedication to a low-carbon future, according to a joint analysis by the Guardian and InfluenceMap.

Funds are often spent through third-parties for much the same reason that Spicer bopped into the bushes — they would prefer not to be seen. Think also of the broad array of companies that portray themselves as climate defenders, while at the same time enabling activist deniers. The list would include utilities and banks. According to Marisa Endicott writing for Mother Jones:

The top four financial institutions supporting the fossil fuel industry are all American: JP Morgan Chase, Wells Fargo, Citi, and Bank of America. Two more, Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs, aren’t far behind. This is despite all six of these major US banks publishing a joint statement, in the months leading up to the adoption of the Paris deal, acknowledging the threat of climate change, pledging financial support for solutions, and calling for a “more sustainable, low-carbon economy.”

To be fair, these banks also finance clean energy projects, e.g., solar and wind, although at lower levels than oil and gas. They’ve also pledged to do increase financing over the next decade or more. The World Bank will be stopping its financing of oil and gas projects after 2019.

What if the organization you and others contribute to is racist or engaged in activities that risk the health and security of society? The world has been warned by climate scientists of the consequences of Earth’s warming, the point beyond which there’s no going back, and that time is of the essence.

Is it ethical then to support an organization like CEI that makes no bones about its denial of climate science and advocates the continued use — no, the expanded and virtually unregulated use of coal and gas — fossil fuels known to cause Earth’s warming and are responsible for respiratory diseases that increase human morbidity and mortality?

Twenty-two states and seven cities are suing the Trump administration over the Affordable Clean Energy (ACE) rule. As reported, the suit alleges that by EPA’s own calculations, the ACE rule, compared to the Clean Power Plan, would lead to 1,400 premature deaths by 2030 and would cost Americans $1.4 billion more per year than it saved. Also, by EPA’s analysis, the $6.4 billion the administration claims will be saved by utilities under the ACE rule would be offset by health costs that run between $16.6 and $75 billion.

The only reason the Trump administration is regulating power sector emissions at all is because of the endangerment finding. The very thing CEI has been trying to get the administration to reverse based on faulty science.

Is believing climate change real and supporting an organization like CEI or Heritage Action just hypocritical, or is it also unethical? Can ethics be considered along a scale, i.e., some acts are a little or a lot ethical depending upon the action and the circumstances?

Are ethics questions binary, i.e., an act is or isn’t ethical? Can unethical practices be offset with a dispensation — say by contributing equal or higher amounts to climate defense organizations, or meeting all energy needs with clean sources like solar and wind?

These are difficult questions to answer. However, I think they’re critically important to consider because the answers will help to determine solutions.

In Google’s case, for example, I have no problem believing that the company needs to stop the rationalizations and the money they give to organizations like CEI and Heritage Action. What Google is doing isn’t illegal. Making it illegal would likely run into a lot of legal difficulties. So, public pressure, e.g., more nurse-ins, articles, and advertising campaigns, might be a good option. Another option would be encouraging and supporting worker strikes — even just for a few hours.

Amazon Employees for Climate Justice led a walkout that, along with its other efforts, led to Jeff Bezos agreeing to step up the company’s efforts to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and a Climate Pledge quite a bit different than the one SPN is encouraging people to sign. Amazon’s pledge commits it to reach a goal of net-zero carbon emissions by 2040.

In other cases, e.g., private investment bank financing of fossil fuel projects, I’m not troubled by the endpoint of reducing to zero the number of oil and gas drilling, pipeline, and coal mining projects financed. What I have mixed opinions about are the best ways for achieving it.

Can it be constitutionally done through regulation? Could it be done faster by getting institutions to lend at higher rates than for renewable projects? Cert-ainly, good cases for higher social costs and higher political, financial, and weather-related risks in a warming climate could be made. Would investor resolutions and lawsuits work? How can it be done without upsetting the economy so much as to send it into recession?

I admit posing these because is much easier than answering them and apol-ogize for not doing so. However, I’m conflicted about some of the answers and would like to hear from readers about what you think.

The one thing I am sure of, however, is that there’s too much hedging going on both in politics and the private market. We’ll never prevail in keeping below the temperature thresholds scientists are warning of by hedging climate defense investments with continuing investments in fossil fuels.

Photo: Screengrab Melissa McCarthy as Sean Spicer on ‘Saturday Night Live’