Turning a Pain in the [Coal] Ash into an Asset

View of the TVA Kingston Fossil Plant fly ash spill, approximately one mile from the retention pond. Courtesy of Wikimedia.

View of the TVA Kingston Fossil Plant fly ash spill, approximately one mile from the retention pond. Courtesy of Wikimedia.

It appears that the reign of Old King Coal is finally ending because of its impact on the environment and its inability to compete economically with cleaner energy sources, including natural gas and renewables like solar and wind.

Coal has powered industries for centuries. Without it, the industrial age was unlikely ever to have begun. According to Christopher Jones, “the rise of coal in the modern era was a global phenomenon, taking place in earnest in Britain beginning in the mid-18th century, the United States and Germany in the early 19th century. Most other nations have followed suit since becoming the world’s leading consumers of coal in the present century.”

Coal comes with a hefty social cost that until recently hasn’t been included in the price paid by consumers. That, too, is changing.

The simple truth is that coal is bad for a nation’s health — starting from when it is extracted to when it is burned and afterward when coal-fired power plants are left with mountains of ash.

Coal ash is the second largest stream of industrial waste in the US, amounting to 70 million tons produced annually[i]. It is incredibly toxic.

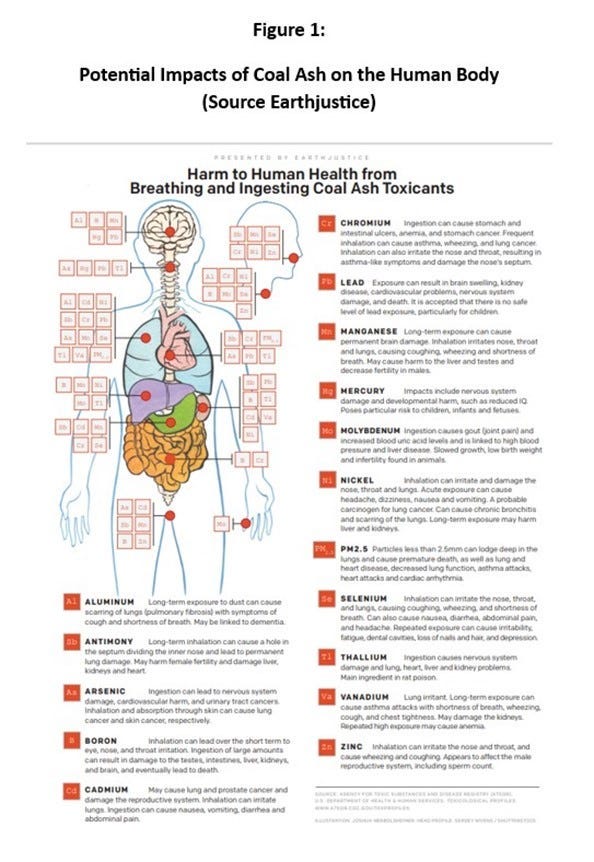

The ash contains at least 17 heavy metals and pollutants, including lead, mercury, cadmium, chromium, selenium, and at least six neurotoxins and five known or suspected carcinogens. The potential adverse impacts of breathing and ingesting coal ash on the human body are extensive. (See Figure 1).

According to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, “the chemical compounds in ash residues can cause skin irritation (dermatitis). Inhalation (breathing in) of these compounds can cause respiratory irritation and irritation of the eyes, nose, and throat. Some compounds found in coal ash are known carcinogens that cause cancer after continued long-term ingestion and inhalation.”

Any of the toxic elements in coal ash can cause serious health issues — in combination, they can be lethal. Exposure to lead can result in brain swelling, kidney disease, cardiovascular problems, and brain and nervous system damage. The impacts of lead and other toxins are particularly harmful to those most at-risk — young and the old.

Coal ash toxins enter the human body primarily through groundwater contamination. They are almost always dumped near water bodies — rivers, lakes, and reservoirs — because coal plants need water for cooling and steam production.

Utilities store the ash residues in ponds, many of which are unlined. Although the unlined ponds pose the greatest risk to potable water supplies through leaching, storm waters can cause the lined ponds to discharge their water-borne toxins into rivers, streams, and wells.

Although federal regulations now require ash ponds to be five feet above the water table, many are below it — increasing the danger of leaks finding their way into potable water supplies. The problem is understandable. When toxins leak out of a pond below the water table, chances are high that they will find their way into wells, streams, and rivers in the surrounding area.

The toxic nature of coal ash has long been understood; however, it wasn’t until 2015 that the US Environmental Protection Agency began regulating coal ash sites nationwide. As is often the case, federal environmental regulation stems from disasters and citizen lawsuits. According to Austyn Gaffney:

“Three days before Christmas in 2008, a coal ash pond in Roane County, Tennessee burst open, releasing 1.1 billion gallons of slurry.”

The ash waters swamped over 300 acres causing millions of dollars of damage. Fifteen years on, the case is still being litigated.

The US EPA issued its final rule on the Disposal of Coal Combustion Residuals from Electric Utilities (hereinafter the CCR) in 2015. It followed more than a decade of litigation by Earthjustice.

The rule establishes nationally applicable minimum criteria for the safe disposal of coal combustion residuals in landfills and surface impoundments.

“In my experience, most power plants have at least one or two coal ash dumps that are not covered by the current rule. This obviously makes groundwater cleanup much harder[ii].”

There is some disagreement over the specific numbers used to define the magnitude of the problem and determine what solutions need to be employed. Unsurprisingly environmental activists and the owners of coal-fired power plants have different notions of what needs to be done — by when and by whom.

Notwithstanding the existence of the CCR rule, federal efforts to regulate coal ash ponds are inadequate. The rule is as notable for what it doesn’t cover as for what it does[iii]:

Of sites and pounds: What the CCR rule doesn’t cover.

· There are at least 372 unlined ash ponds within five feet of groundwater. Of these, 172 have been or will be closed by removal and transport. The remaining 200 are closing in place.

· A study of 292 regulated coal plants by Earthjustice and the Environmental Integrity Project (EIP) found that 265 (91 percent) are contaminating ground waters in 43 states. The researchers also established that 123 (46 percent) of the plant owners do not plan any remedial action.

· At least 170 coal ash ponds in the US benefit from a loophole in the CCR. The rule does not apply to power plants that stopped generating electricity before October 2015. These are commonly referred to as legacy ponds.

· In addition to the ponds on power plant properties, 500 million tons of unregulated coal ash are in close to 300 inactive landfills nationwide.

· Researchers have also calculated that 70 percent of the power plants with ponds they intend to close are disproportionately located in communities of low income and color. Communities of color and low income have historically been the sites of a disproportionate number of coal-fired power plants and landfills.

· The 299 coal-burning plants remaining in the US generate almost 70 million tons of new ash each year.

Beyond loopholes, there is the matter of enforcement. The CCR comes under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), which places much of the enforcement burden on state agencies.

According to Frank Holleman, a senior attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC),

“No state agency anywhere has filed an enforcement action against any utility, under the 2015 rule, even though we’ve seen widespread failure to comply.”

Holleman contends that states don’t want to enforce the law because of their relationship to utilities. However, other reasons have to do with being understaffed and politics.

Truth be told, the US EPA hasn’t done much enforcement either until recently. Here, too, there are real-world reasons. Not the least of these concerns is changing administrations and congressional majorities. EPA has finally become a more active and attendant enforcer of the CCR.

The Agency denied just three coal plant disposal requests in all of 2022. In January 2023, EPA administrator Michael Regan indicated that the Agency has already opposed six requests to continue “disposing of coal combustion residuals (CCR or coal ash) into unlined surface impoundments.” Regan went on to say:

EPA is holding facilities accountable and protecting our precious water resources from harmful contamination, all while ensuring a reliable supply of electricity to our communities.

Enforcement of the CCR is consistent with President Biden’s climate priorities and a complete reversal of the Trump administration’s position on coal and coal ash. The politicization of climate change and efforts to brand it as woke drags environmental regulation to almost a net zero.

Every time an administration reverses a set of regulations, it’s a new rulemaking and subject to the Administrative Procedures Act (APA). Between the APA and lawsuits, it can take years to accomplish a regulatory objective. In the interim, industry, state, and local governments have reasons not to do anything.

Since 2015, citizen lawsuits by environmental, civil rights, and community groups most threatened and impacted by coal-ash ponds have driven enforcement of the rule. The legacy pond loophole will likely be closed because of a court challenge[iv] brought by Earthjustice.

Many environmental experts believe the best way to prevent water pollution due to coal ash storage is to dig it up and take it elsewhere. Recall that 372 unlined ash ponds are within five feet of groundwater, and hundreds are spilling and leaching their contents into ground waters, rivers, and lakes.

Digging and transporting coal ash comes with substantial dollar costs and environmental risks. Although estimates vary, it’s clear that digging and transporting by truck or train is no small undertaking. Chloe Hills, writing in Energy News, suggests that a coal pond on TVA’s Allen Fossil Plant contains 3.5 million cubic yards of toxic ash that needs to be moved to a lined landfill 19 miles away.

TVA estimates it will take 120 daily loads of 17 cubic yards to haul the ash out of the Allen facility. Since each truck will make an up-and-back trip, the total daily truck trips will be 240. Over the course of 210 days, the total number of truck trips is 50,400. If you add to this figure the number of up-and-back trips with dirt to fill in what’s left in the wake of the ash, the estimated number of trips nearly doubles.

It’s doubtful that all 100,000 truck runs will go smoothly. Trucks break down, become involved in accidents, and lose their covers, resulting in airborne toxins landing in streams, lakes, and rivers. Trains are sometimes an alternative to trucks, but as the nation saw recently in East Palestine, Ohio, hauling by train also has its risks.

On April 11th, a truck hauling 40,000 pounds of soil contaminated by the East Palestine train wreck overturned, spilling half its contents. The accident occurred away from the original accident site expanding the danger zone to other parts of the county.

Trucking hazardous coal ash from one place to another comes with its own environmental problems. The trucks used to haul the coal ash are themselves a significant source of greenhouse gases, e.g., carbon and airborne particulates.

The average dump truck gets between five and six miles per gallon. According to the Badger Truck and Auto Group, most dump trucks will use 415 to 500 gallons of diesel fuel per week. The US Energy Information Administration estimates that 22.45 pounds of CO2 are produced by burning a gallon of diesel fuel.

Transporting coal ash from one site to another adds to the overall contribution of the transportation sector to Earth’s warming. The transportation sector is the single greatest source of greenhouse gas emissions. It is responsible for 28 percent of overall emissions.

There is another aspect of hauling coal ash from one place to another to consider. Many US coal-fired power plants are located close to communities of color and low income. Moreover, many receiving landfills are also disproportionately sited in at-risk communities.

These communities bear the brunt of the digging and hauling needed to safely remove and repair coal ash ponds that threaten water quality. When the Tennessee Valley Authority decided to move ash from its Allen Plant in Memphis, it considered seven landfills. Nearly all — including the final resting place of the ash — were in communities of color and low income.

Environmental experts generally believe digging and hauling coal ash is the best solution for fixing the problem of leaking coal ash ponds. However, there are alternatives.

…coal ash in encapsulated form provides important benefits to the environment and the economy[v].

According to the EPA, encapsulated coal ash can beneficially replace virgin materials removed from the earth, conserving natural resources “Encap-sulation involves preventing it from escaping by binding it to or in something else[vi].”

Currently, the two primary uses of fly ash are as a substitute for cement in reinforced concrete mixes and wallboard. Overall, it’s estimated that 35 to 40 million tons of coal ash are beneficially used annually — depending mainly on the health of the construction sector. It’s hardly an amount at which to sneeze.

To put that number into perspective, the US annually produces around 70 million tons of the stuff. The environment would clearly benefit from more opportunities to repurpose coal ash into sustainable products.

“The best solution to disposal problems is to quit throwing it away.[vii]”

What if encapsulated coal ash could assist solar and wind energy resources to avoid their intermittency problem? It’s hardly a hypothetical question, as a company has patented an energy storage system that combines the beneficial use of coal combustion residuals (CCR) with a low-profile pumped storage hydro system (PSH).

Krubera, LLC is proposing a new patented use for CCR. The company’s design encapsulates on-site coal residues in a pumped-storage system that helps to solve the intermittency problem associated with solar and wind power technologies.

Because the system reduces the need to dig up the CCR in unlined or leaking ponds and take it elsewhere, it cuts down the cost and reduces the risks inherent in such operations. It ends up being a win for the utilities, ratepayers, at-risk communities of color and low income.

Innovation is not always about new technologies. It is also about finding better ways to utilize the things that are available.

This is Part 1 of Turning a Pain in the [Coal] Ash into an Asset. In Part 2, I’ll be going into more detail about the Krubera system and how it matches up against federal regulations

******************************

[i] Estimates vary between 70 and 130 tons.

[ii] Abel Russ, a senior editor with Environmental Integrity Project

[iii] “Poisonous Coverup: The Widespread Failure of the Power Industry to Clean Up Coal Ash Dumps,” by the Environmental Integrity Project and Earthjustice.

[iv] Solid Waste Activities Group v. Environmental Protection Agency (DC Cir. 2018) (the “USWAG case”).

[vii] John Ward, chair of Citizens for Recycling First and executive director of the National Coal Transportation Association.