Trump’s Environmental Legacy Will Take Time to Erase

I have an Article 2 where I have the right to do whatever I want as president

I have an Article 2 where I have the right to do whatever I want as president

— Donald Trump

Time is the dearest resource we have in the fight to combat Earth’s warming. Whether there is time enough to avoid the harsh economic and environmental consequences waiting beyond the 1.5 degree Celsius threshold scientists warn is a point of no return mostly depends on what the US and the other nations of the world choose to do about the climate crisis and when they will choose to do it.

Time is the fixed element of the warming response equation. It can neither be manufactured nor stopped. Idle time can’t be saved in a rainy-day account or the loose change jar on your dresser to be used later.

Although time past can’t be retrieved, tomorrow’s time can be mortgaged — as it has been by Trump’s efforts to deregulate the nation’s environment and continue its addiction to fossil fuels.

Undoing the damage done by Trump to the environment and the regulatory framework that protects it will prove more difficult — certainly more time consuming — than moderate and progressive climate defenders imply in their various green policy proposals.

The way forward for any climate defense plan — moderate or progressive — is going to be cluttered with the refuse of the Trump administration, e.g., rolled back regulations, extant lawsuits, the lost government offices and programs needed to implement a pro-environment agenda. Cleaning up what Trump and company will leave in their wake is going to take time, as will putting in place a comprehensive climate defense plan.

There is time, and then there is government time. As Trump has discovered the rules of law govern what and how the federal government does its bus-iness. Whether rescinding or implementing a regulation, the federal govern-ment is required to comply with the Administrative Procedures Act (APA). Either action can take two to seven years to accomplish — depending on whether it is challenged in court.

Time requirements need to be factored into the implementation estimates of the various green deals being proposed by 2020 candidates running for Cong-ress and the White House. These requirements also need to be made part of the dialogues between lawmakers, advocates, and their respective constituencies, who are eager for change. In the current, highly contentious political atmosphere delays of a year or more can be wrongly interpreted as a lack of commitment or gamesmanship by “establishment actors.”

This is the first installment of a periodic series focusing on the political and legal challenges a Democratic president elected in 2020 — President X — should be prepared to face starting on Day 1 of their administration if the nation is to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 or sooner.

The installment focuses in some detail on what the Trump administration has done through the exercise of presidential powers, i.e., executive orders, and the ease or difficulty President X can expect to encounter in rescinding and replacing those orders. Time requirements will be highlighted throughout the discussion — as they will be throughout the series.

By the time a newly elected Democratic president — President X — is sworn into office on January 20, 2021, Trump will have had four years to under-mine the nation’s environmental protection framework. Time enough to rescind and revise the entirety of the Obama administration’s air and water rules, as well as issuing hundreds — perhaps thousands — of pipeline permits to oil and gas concerns and hawking federal lands to fossil fuel companies for exploration and extraction of the very energy sources known to cause Earth’s warming.

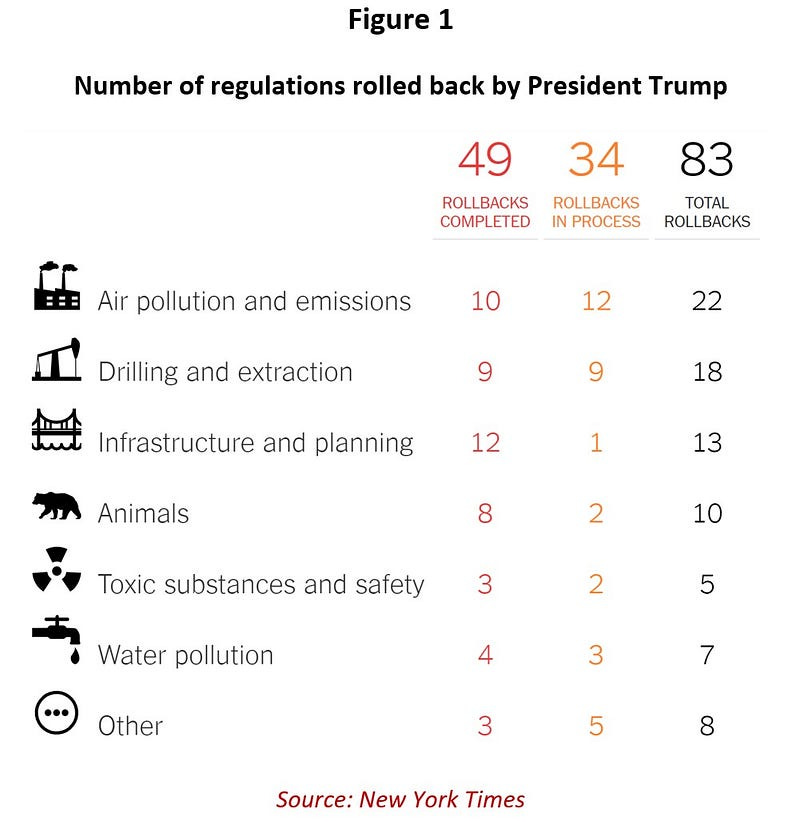

Two and a half years into his first term, Trump can boast of having rolled back or being in the process of rolling back 83 climate-related regulations. (See Figure 1) Beyond the boast, the administration has opened federal lands to oil and gas drilling. It looks to do the same for coal despite a recent setback in the courts.

The Trump administration has leased the oil and gas rights of close to 378 million acres (153 million hectares) of public lands and waters through April 2019. More leases are in the offing.

The standard federal lease period is ten years, which means lands leased by the Trump administration could still be giving up their fossil fuel reserves into and beyond President X’s second term ending in 2028.

The Wilderness Society estimates that the leases already issued by the Trump administration have the potential to emit between 854 million and 4.7 billion metric tons (MT) of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e). These lifecycle totals exceed than the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of all 28 EU member countries. Accounting for the potency of shorter-lived climate pollutants like methane, lifecycle emissions from the development of these leases could be as high as 5.2 billion MT CO2e.

The nature of executive power

The gridlock that has gripped Congress for most of this century forced presidents Obama and Trump to pursue their opposing environmental agendas through unilateral executive actions. Although presidents cannot make law, they can order executive agencies to act within the law to achieve certain specified ends.

The power of the presidency vests through Article II of the US Constitution. Some presidential powers can only be wielded with the advice and consent of the Senate, e.g., making treaties and appointing Supreme Court justices.

Other powers are considered inherent to the office, e.g., declaring a state of emergency in the aftermath of a hurricane. Presidents have historically exercised their authority through several written instruments — executive orders, memoranda, and proclamations. [i]

According to the Congressional Research Service (CRS):

… the definitions of these instruments, including the differences between them, are not easily discernible, as the U.S. Constitution does not contain any provision referring to these terms… The only technical difference is that executive orders must be [numbered and] published in the Federal Register, while presidential memoranda and proclamations are published only when the President determines that they have ‘general applicability and legal effect.’

The advantage of these instruments is the ease with which they can be written. All that’s required is a pen, paper, and a willing president. The disadvantage of these instruments is the ease with which they can be rescinded by a different president, with another pen, and a new piece of paper.

Although having the force of law, executive directives can’t circumvent applicable laws and regulations. For example, Trump’s ordering the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to scrub the books of President Obama’s Clean Power Plan doesn’t permit the Agency to do so outside the requirements of the Administrative Procedures Act, e.g., publishing the appropriate rulemaking and revising notices in the Federal Register and soliciting public input.

Equally, as President Trump has been learning, executive orders are subject to judicial review both for their compliance with the US Constitution and applicable statutes. The US District Court for the District of Alaska held in League of Women Voters v. Donald J. Trump and the American Petroleum Institute that Section 5 of Trump’s Executive Order 13795 — Implementing an America-First Offshore Energy Strategy — was unlawful and invalided the section. The Order was issued on March 28, 2017.

The case was one of dueling executive orders. President Obama had issued three memoranda and one executive order withdrawing certain areas of the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) from [oil and gas] leasing. The areas affected were portions of the OCS in Alaska’s Beaufort and Chukchi seas and canyon areas in the Atlantic. Trump sought to rescind President Obama’s withdrawal, thereby opening the areas to oil and gas exploration and extraction.

The judge in the case applied basic principles of statutory construction in interpreting the language of Section 12(a) of the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act. The court noted that while Congress authorized presidential withdrawals under the Act, it did not expressly delegate a president the authority to reverse a withdrawal order.

As of August 7, 2019, the case is on appeal to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. More than two years after Trump’s issuing the Executive Order, it remains to be carried out.

There’s time, and then there’s government time

Federal executive agencies carry out presidential directives in much the same manner as they do the legislated mandates of Congress. In both cases they are charged with the task of putting in place implementing regulations.

Whether at the behest of the president or Congress, federal rulemaking is subject to the dictates of the Administrative Procedures Act (APA). Following APA procedures takes time — a lot of time. The League of Conservation Voters involved only the rescission of an executive order and an agency’s effort to lease lands in the Atlantic and Arctic Oceans — essentially a straightforward two-step process.

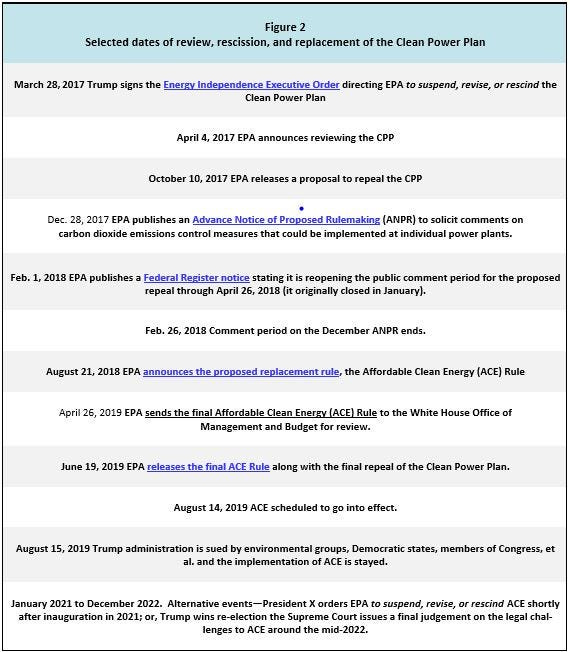

Implementing a whole new regulatory scheme can involve much longer lead times — possibly as long as five or more years. Consider, for example, Trump’s Executive Order (E.O.) 13783. It is the directive that led to the rescission of President Obama’s Clean Power Plan (CPP) and the issuance of Trump’s Affordable Clean Energy rule (ACE).

The Order was signed on March 28, 2017, a month before the offshore order. It directs the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to review the final CPP rule against the backdrop of the administration’s newly stated policy:

…that executive departments and agencies (agencies) immediately review existing regulations that potentially burden the development or use of domestically produced energy resources and appropriately suspend, revise, or rescind those that unduly burden the development of domestic energy resources beyond the degree necessary to protect the public interest or otherwise comply with the law.

E.O. 13783 also declares it in the national interest to promote clean and safe development of our Nation’s vast energy resources, while at the same time avoiding regulatory burdens that unnecessarily encumber energy production, constrain economic growth, and prevent job creation.

Figure 2 lists the progress to-date of EPA’s efforts to replace the CPP with the Trump administration’s ACE rule. It also offers an estimate of final outcomes that could occur between 2019 and mid-2022 or later. Although it is possible that the US Supreme Court will decide in favor of the Trump administration and the ACE rule will go into effect before the 2020 election, it is the least likely alternative.

The more likely path the case will follow depends on the outcome of the 2020 election. If the Democrat wins in 2020, then President X will order EPA to review and, most probably, rescind ACE.

Alternatively, if Trump remains in office and no decision by the High Court has yet been made, the case could drag on for several months or more into 2021 — possibly on into 2022. The passage of time plays into both of these potential outcomes. In neither case is the outcome positive.

The next installment of the series begins a discussion of the impact of these delays on meeting the US’s commitments under the 2009 Copenhagen Accord and the 2016 Paris Agreement. It also begins an examination of the differences between the Clean Power Plan and Affordable Clean Energy plan, as well as other potential policies that will be in force over the next five to ten years.

**********************

[i] Other written instruments have historically included administrative orders, homeland security presidential directives, letters on tariffs and international trade, for example. For more background, see CRS Report 98–611, Presidential Directives: Background and Overview, by Elaine Halchin.

Lead photo courtesy of Unsplash at https://unsplash.com/@knobelman