Trump Climate Policy-The Lawlessness of It All

As the nation struggles to free itself from the grip of the coronavirus contagion and a disease of a different sort — racial, economic…

As the nation struggles to free itself from the grip of the coronavirus contagion and a disease of a different sort — racial, economic, and environmental injustice — our president continues to lay waste to the country’s environmental protections.

The COVID-19 contagion shows once again the disdain President Trump and his administration have for science-based policies and actions. Over the past several months, Trump has suggested that the coronavirus would just go away in the heat of the summer, touted his natural genius for the practice of med-icine, and implied that a Clorox cocktail might make the sick well again. His outlandish statements about the contagion closely parallel those he’s made about the scientific basis of climate change — its origins and solutions.

As I’ve written before, Trump has used the coronavirus as a convenient cover to continue his assault on the nation’s environmental framework. His most recent attack comes in the form of an executive order with the objective of giving federal agencies the authority to waive the preparation of environ-mental impact studies pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). The president’s Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) describes the Act this way:

NEPA was the first major environmental law in the United States and is often called the “Magna Carta” of Federal environmental laws.

Section 101 of the Act sets forth a national policy in words befitting of the Green New Deal:

The Congress, recognizing the profound impact of man’s activity on the interrelations of all components of the natural environment…the…influences of population growth, high-density urbanization, industrial expansion, resource exploitation, and new and expanding technological advances…declares that it is the continuing policy of the Federal Government…to use all practicable means and measures, including financial and technical assistance…to foster and promote the general welfare…to create and maintain conditions under which man and nature can exist in productive harmony and fulfill the social, economic, and other requirements of present and future generations of Americans. (emphasis added)

NEPA minimally requires federal agencies to consider the environmental effects of proposed major Federal actions before any final decision is made. The Act is technology-neutral. It requires an analysis of the environmental consequences of siting the eight largest solar power facility in the world (Gemini) on federal lands just as it does for granting the Keystone XL pipeline a right-of-way across government property.

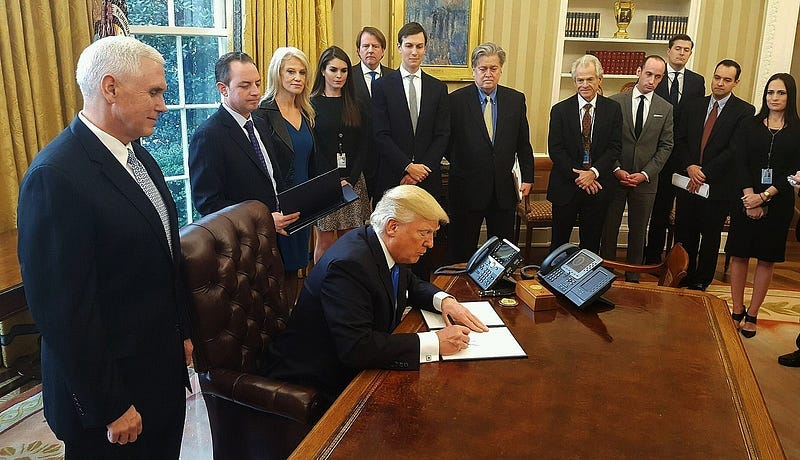

Trump has found executive orders much to his liking, as they offer him an opportunity to avoid having to deal with pesky House Democrats — especially on climate matters. In a deeply divided Washington, the nation’s chief exec-utives have often resorted to the use of presidential orders and memoranda to accomplish on their own — if only temporarily — what they couldn’t do with the Congress.

Trump came into office hellbent on unwinding the entirety of President Obama’s environmental legacy. A legacy, it should be noted, largely ac-complished via executive action. This most recent order looks to unwind environmental protections dating back to before President Nixon.

Executive orders have the status of law, but only for as long as they remain on the White House’s books and, therein, lies their weakness. As convenient as it is for one president to issue an order, is the ease with which a successor can revoke it.

Should Biden win in November, I don’t doubt he’ll retract the whole of Trump’s climate-related orders within minutes of his sitting down behind the Resolute desk — furniture which the 45th president has become fond of but about whose provenance he remains befuddled. In the meantime, federal agencies and departments will do as much they can to commence and continue projects without the nuisance of having to contend with NEPA requirements. In response, environmental advocates will file as many lawsuits as they can to keep agencies on the straight and narrow when it comes to complying with the law.

The executive order with the fancy name of EO on Accelerating the Nation’s Economic Recovery from the COVID-19 Emergency by Expediting Infrastructure Investments and Other Activities is more fluff than substance. In fact, it is so poorly conceived and written that it is unlikely to be upheld by the courts.

Like any law, executive orders are subject to judicial review. A circumstance Trump and his administration have been confronted with on numerous occasions much to their chagrin.

In the (COVID-19) Emergency Order, Trump states that measures like social distancing and other mitigation strategies have brought down the economy. The Order doesn’t give government officials any new authority. It simply encourages them to use the powers otherwise provided in existing laws like the Endangered Species (ESA) and Clean Water (CWA) Acts.

By almost any reading, there is nothing to suggest that the crafters of the legislation ever contemplated a flagging economy and high unemployment due to a health crisis as a reason for emergency action. As Holly Doremus, the James H. House and Hiram H. Hurd Professor of Environmental Regulation at UC Berkeley points out:

No one thinks NEPA analysis or ESA consultation should be required before the government responds to an act of war, or fights a conflagration, or rescues people from a flood. Those are the circumstances these exceptions target.

Guidance on Emergencies and the National Environmental Policy Act issued by CEQ confirms Professor Doremus’s conclusion. The Council recognizes there will be times when immediate threats to human health or safety, or immediate threats to valuable natural resources require extraordinary responses. (emphasis added)

In its guidance, CEQ is careful to point out that alternative arrangements do not cover long-term response and recovery actions. Neither do they necessarily free an agency from other of the Act’s requirements like notifying and informing affected public, state, regional, Federal and tribal representatives that would be impacted by the proposed actions. Clearing the way for the construction of pipelines, large solar installations, and other such infrastructure projects cannot reasonably be said to be the type of emergency actions contemplated by the Act.

The Order is based on what some legal experts believe is an intentional misreading of the emergency provisions of various environmental laws like the Endangered Species and Clean Water Acts. Moreover, CEQ’s warns the agencies that alternative arrangements under 40 CFR § 1506.11 may be subject to judicial review.

In the midst of the millions of marchers in the US and abroad calling for an end to racial injustice, Trump has dubbed himself the law and order president. It is a tag much at odds with his environmental actions.

The issuance of the attempted NEPA suspension order is further proof of Trump being the chaos president. The directive appears to be a deliberate attempt to introduce yet more uncertainty into the nation’s environmental protection laws. Although the administration cannot amend the Act outright, it can muddle its operation. Rather than expediting a pipeline or other infrastructure projects, the directive almost guarantees delays due to lawsuits. Delay and obfuscation are typical Trumpian tactics the President has employed to get his way — both in and out of the Oval Office.

Private companies will undoubtedly think twice about getting involved in any projects subject to NEPA review given a waiver under the Order. The projects will either never be started before a court steps in to order the administration to conduct the required environmental studies or, once started, stopped pen-ding their production. By law, impact statements must also include oppor-tunities for public input — another requirement considered anathema by Trump and company.

The administration’s less than stellar record of defending its environmental actions in court should be enough to raise activist eyebrows. It has often lost in court for its irrational failure to follow well-established administrative procedures. Under such circumstances, it would appear the administration is as content to throw a spanner into the workings of government as it is to do things according to Hoyle.

Trump — whether as a real estate developer or president — has consistently engaged in lawlessness of his own making by refusing to accept the “riotous” concept that he is not above the law. According to USA Today, Trump and his businesses[i] have been involved in at least 3,500 legal actions in federal and state courts during the past three decades. They range from skirmishes with casino patrons to personal defamation lawsuits. The thousands of lawsuits Trump faced as a businessman and the hundreds his administration has already had to defend against in court exhibit a pattern of intentional lawlessness.

Whether Trump leaves office at the end of four years or eight, his successor will be faced with a tangled web of environmental regulations — some in force but many others in court. Although a climate-conscious president will be able to rescind Trump’s various executive initiatives and directives with a stroke of the pen, it will take years to reverse the actions taken by agency heads pur-suant to those orders let alone to put in place the defense framework needed by the nation to protect against and adapt to the ravages of Earth’s warming temperatures.

It is fair to conclude that President Trump will be viewed as the worst environmental president in history and that he became so by finding ways to weaponize time.

*************

[i] As of 2015.