Trump and Mother Nature Threaten to Sink Rural America-

What Does It Mean for the Democrats in 2020?

What Does It Mean for the Democrats in 2020?

Farmers and ranchers are hurting, and there are pockets of this country where the economy is not strong. — a GOP lawmaker

Trump’s crowing about his having launched an unprecedented economic miracle rarely seen before belies the harms his economic and environmental policies are causing farmers, ranchers, and agro-businesses in America’s heartlands. Consequently, Trump and the Republican Party may find themselves victims of climate change come election day 2020. If it happens, their defeat will have been significantly contributed to by the loss of a key core constituency — rural voters.

Combined with the growing number and intensity of climate-related natural disasters Trump’s trade wars with China, Mexico, Canada, and the European Union have put American farmers — particularly family farmers in Midwestern and Plains states — in a much-weakened economic position.

As reported, the White House’s acting chief of staff explained why voters would continue to support Trump’s run for a second term:

You hate to sound like a cliché, but are you better off than you were four years ago? It’s pretty simple, right? It’s the economy, stupid. I think that’s easy. People will vote for somebody they don’t like if they think it’s good for them.

Ask America’s farmers if they are better off than they were four years ago. The numbers say no:

Personal income for farmers is down 25 percent this year — the steepest decline since the first three months of 2016.

Since 2010 farm incomes are down 11 percent, while expenses are up 31 percent because of falling commodity prices and China’s reduced demand due to Trump’s on-going trade war.

Farmer bankruptcies in 2018 rose 30 percent in the six Midwest states covered by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

Farmland prices, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas look to decline — unlike in the last downturn when land values remained reasonably stable.

The Trump administration put aside $12 billion in 2018 to compensate farmers for their losses due to the trade war with China. Reports are mixed as to whether the funds offset the losses as the battle has worn on — and on. Even if there were sufficient funds to cover their losses, most farmers would say federal compensatory dollars are no substitute for market sales.

America’s soybean producers may also tell you that China, traditionally the largest purchaser of US soybeans, is taking part if not all its $12–14 billion in soybean purchases elsewhere. In 2017, the US sold nearly 32 million metric tons of the stuff to China.

Due to Trump’s trade war, China reduced its soybean purchases in 2018 by 74 percent of 2017 levels. By November 2018 China completely stopped purchasing US soybeans. According to the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), the equivalent of about 80% of the total US harvest last year was sitting in storage at the end of the year.

Grant Kimberley, director of market development at the Iowa Soybean Association, has indicated the worst may yet to be. Although China pledged last December and again this past February to place big orders, the promised purchases would only amount to two-thirds of the 2017 level.

To date, the administration has ordered three rounds of tariffs on Chinese goods totaling more than $250 billion. Trump recently threatened to increase tariffs from 10 percent to up to 25 percent on $200 billion of additional Chinese goods — if a deal isn’t in place by 12:01 a.m. on Friday, May 11th. Farm-state members of Congress are concerned that Trump’s recent threat will once again trigger Chinese retaliation.

China is not the only country to have levied retaliatory agricultural tariffs since Trump began levying tariffs on foreign goods and services to make America great again. According to the Congressional Research Service:

China, the European Union (EU), Turkey, Canada, and Mexico. U.S. exports of those products to the retaliating countries totaled $26.9 billion in 2017, according to USDA [US Department of Agriculture] export data. The choice of agricultural and food products for retaliatory tariffs likely reflects the large volume of agricultural trade involved and that many of these products can be sourced from non-U.S. trading partners.

Due to retaliatory tariffs China has fallen from the leading export market for U.S. agricultural products in FY2017 to the third in FY2018 and is forecasted to fall to fifth place in FY2019, according to the US Department of Agriculture.

Equally concerning to farm-state voters and politicians is Trump’s efforts to swap out the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) for the newly negotiated U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). The new agreement faces Congressional opposition largely from Democrats over the lack of labor and environmental protections in the new agreement.

Republican senators meeting with Vice President Pence have expressed concern that Trump may threaten to pull out of NAFTA before the new agreement is ratified as a means of getting what he wants. Given the way Trump’s game of chicken with China is playing out, the concern has merit.

Midwestern farmers have been storing their corn and soybeans in unprecedented amounts due to the U.S. and China trade war, according to the BBC. Now the waters are rising around those stored grains thanks to climate-related weather events that have dumped unprecedented amounts of water on parts of the Midwest. Unfortunately, the $12 billion set-aside assistance to cover trade war losses cannot be used to compensate the owners of grains damaged by rising river waters.

Federal policy requires those stores to be destroyed and according to Reuters, there’s nothing the U.S. government can do about the millions of damaged crops under current laws or disaster-aid programs. It’s not just rotting grains in storage that account for the huge economic losses being incurred across rural America.

All six of the top corn-producing states are now behind schedule as far as this growing season is concerned. Even before the recent flooding in Nebraska and Iowa planting across Illinois, Indiana, Minnesota and South Dakota — states that account for 40 percent of US corn supplies — was already behind schedule. The April and May’s rains in Nebraska alone are causing over a billion dollars in losses according to Governor Pete Rickets (R-NE) — at least half of those sums are lost livestock.

The magnitude of destruction caused by climate-related weather events is of a scale never seen in the US. AccuWeather estimated the total damage and economic loss caused by record-breaking flooding in the Midwestern U.S. this spring would total $12.5 billion. It is hardly the first time in the past few years that US agricultural lands have been impacted.

According to Sam Bloch at the New Food Economy

Over a period of 10 months in 2017, America experienced 16 separate, billion-dollar weather and climate-related disasters. Those weather events carved paths of destruction straight through some of the most fertile and productive regions of the country, wreaking havoc on beef cattle ranches in Texas, soaking cotton and rice farms in Louisiana, orange groves in Florida, and burning up vineyards in California. And that was all before Southern California’s still-active Thomas fire, which began on December 4, and then closed in on the country’s primary avocado farms. It’s now the state’s largest-ever, in terms of total acreage.

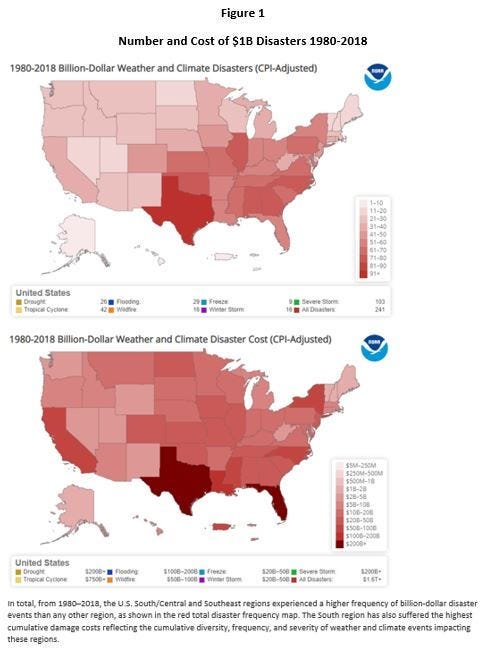

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) counted 14 billion-dollar weather and climate-related disasters in 2018: two tropical cyclones, eight severe storms, two winter storms, drought, and wildfires. The past three years (2016–2018) have been historic, with the annual average number of billion-dollar disasters being more than double the long-term average. The number and cost of disasters are increasing over time due to a combination of increased exposure, vulnerability, and the fact the climate change is increasing the frequency of some types of extremes that lead to billion-dollar disasters. (See Figure 1)

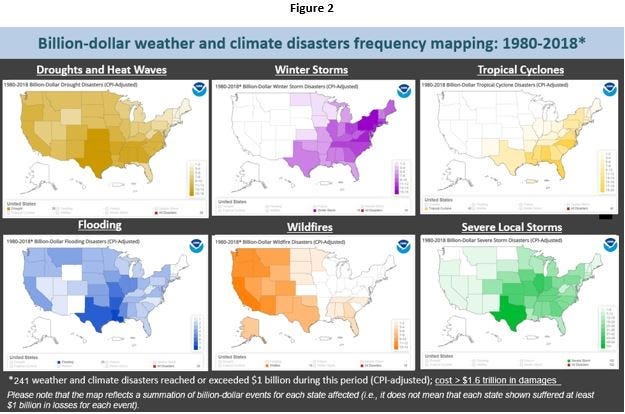

Figure 2 illustrates the frequency by type of billion-dollar weather and climate disaster in each state.

Weather-related natural disasters are not the only problems facing those whose living is tied to the land. Extinction of bee populations, the loss of plant species due to both changing habitats, turning forests into grazing lands and industrial monoculture, water pollution due to oil and gas operations, including pipeline leaks, all threaten the future of American farming.

Add to the myriad negative consequences of weather-related disasters the loss of overseas markets for US agricultural commodities and the list of reasons why rural voters may think twice before voting for Trump and down-ballot candidates for the House and Senate in 2020.

Trump’s victory in the 2016 presidential elections came about largely because of his strength in America’s middle-farmlands and southeastern coastal states. Rural voters have been steadily moving towards Republican ranks. Figure 3 shows rural voters to be the largest block of Republican support by percentage.

Because of the Electoral College system under which the US operates Trump was able to lose the popular vote by just under 3 million votes while still capturing the White House. (Figure 4)

The Electoral College system, in practice, values the votes of some greater than others. One can argue the fairness of the system and whether the Founders’ premise for doing so remains valid after 232 years. The fact remains that the system is not going to change anytime soon — certainly not in time for the 2020 election.

Is it still the economy, stupid?

Rural voters are among Trump’s most tenacious supporters and still, show themselves loyal. Consider the words of Trump’s acting chief of staff Mick Mulvaney again:

It’s pretty simple, right? It’s the economy, stupid. I think that’s easy. People will vote for somebody they don’t like if they think it’s good for them.

The central question here is if it is the economy — will people vote for somebody they do like if it’s not good for them?

First, consider that Mulvaney’s aphorism is wrong in terms of the 2018 House elections. The economy in 2018 was strong and Trump’s suburban voters — especially educated affluent women — bolted on him. Of the 40 congressional districts that Democrats turned from red to blue in 2018, 38 were suburban.

As I’ve written before, forty percent of Congressional districts are comprised mainly of suburban communities. Once decidedly more Republican than Democrat, the suburban rings around major cities across the country are showing themselves more evenly divided but with a distinct portside tilt. In the 2016 election, 49 percent of suburban voters cast their lots with Trump, while 45 percent did the same with Clinton. Just two years later, suburban voters sent a majority of Democrats to the US House of Representatives.

If Mulvaney is right about the economy outweighing voters’ personal preference and political ideology, then Trump’s in a boatload of trouble — as his boat is sailing the floodwaters of America’s rural heartlands.

The earlier referenced meeting between Republican senators and Vice President Pence on concerns about Trump’s trade wars with China, Canada, and Mexico is only one example of growing Republican rumblings on and off Capitol Hill. Rumblings that are as much about the 2020 elections as they are current trade negotiations.

Once staunch Republican deniers and resistors are also changing their tunes on climate change. On Earth Day 2019 Senator Lindsey Graham (R-SC) — a recent rarely questioning ally of Trump — announced that congressional Republicans are ready to cross the Rubicon on climate change.

In recent weeks it has been reported by Bloomberg, the New York Times and others that Senator John Cornyn of Texas — an oil state where climate denial runs deep — said he is helping write legislation to reduce emissions through “energy innovation.” Senator Lamar Alexander of Tennessee said he wants to create a “Manhattan Project” for clean energy funding. Senator Lisa Murkowski of Alaska is exploring bipartisan plans to curb emissions from her position as chair of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources. And Representative Matthew Gaetz of Florida, who once called to abolish the Environmental Protection Agency, introduced legislation to tackle climate change by encouraging nuclear energy and hydropower, as well as “carbon capture” technology, which aims to pull planet-warming carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. (see also here and here)

How rural Americans will vote in 2020 remains anyone’s guess. Their loyalty to Trump should not be underestimated — but neither should their willingness to vote their economic interests be ignored.

The fortunes of US climate policies have largely depended on the occupant of the Oval Office and the courts. However, the courts are too slow to act and, the presidency is too flighty. The only way the nation can ever hope to keep from crossing the warming thresholds climate scientists are warning of is by breaking free of partisan gridlock.

Even within the current bitter partisan environment on Capitol Hill the issue of climate change and the increasingly urgent need to do something about it has begun to gain traction. Why? Because today climate-change awareness is disaster driven.

Because of Trump’s trade policies and the increasing frequency and severity of billion-dollar weather-related disasters across the middle of America, Democrats have an opportunity to bridge the urban-rural divide and bring voters on both sides of the aisle to the side of the environment.

Mulvaney is wrong. It is not the economy, stupid; it’s the environment. Only when the US puts in place the climate defense framework needed to combat Earth’s warming will the nation’s economy ever be on a solid foundation.