The Affairs of States: In the Greening of America

The environmental problems we face are deep-rooted and widespread. They can be solved only by a national effort embracing sound…

The environmental problems we face are deep-rooted and widespread. They can be solved only by a national effort embracing sound, coordinated planning and effective follow-through that reaches into every community in the land. Improving our surroundings is necessarily the business of us all.

- Richard Nixon

· Hyper-partisanship is not just Washington’s affliction. We remain a nation of red states and blue states.

· President Biden has put forward an aggressive plan with which to combat Earth’s warming. If the immediate past is prologue, there will be little permanence to anything his administration manages to accomplish absent Congressional action.

· There was a time when Republicans and Democrats managed to work together — or at least to tolerate each other long enough to enact needed environmental protections.

· Politics are not the only thing that’s local. The consequences of climate change are being felt first and most acutely at the state and local levels.

· Will proximity to the problem bring red and blue states into alignment on what needs to be done?

As a creature of Washington, I naturally follow federal affairs. Too often, I do this to the exclusion of the affairs of states. To mend my ways, I’m starting an occasional series of articles focused on the goings-on at the state, county, and city level.

This first installment looks to provide a bit of historical and political context on the federal-state relationship regarding environmental matters and how it has changed over the past half-century. It is a transformation largely borne of hyper-partisanship and two decades of congressional gridlock.

Federalism is not what it used to be.

The cornerstones of America’s environmental protections were laid in the 1960s and 1970s. Stoked by a burning Ohio river and an oil spill off the California coast, it was a time of rising public consciousness of environmental problems and the belief that federal involvement was needed.

Most importantly, it was a time when Republicans and Democrats in Washington worked together to address national issues. Nixon stands as the greenest president in US history. He earned the title working with the Democratically controlled 91st and 92nd Congress.

Nixon’s “brilliance” was not his love of nature — for there’s much to suggest abject indifference or outright disdain — but in his recognition of the political salience of environmental protection.

Nixon and Congress worked together to enact the laws that a half-century later remain the foundation of US environmental policy. They include:

· National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA/est. Council on Environmental Quality)

· Created the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

· Clean Air Act Extension of 1970 (CAA)

· Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 (MMPA) Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act of 1972 (MPRSA)

· Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974 (SDWA)[i]

· Endangered Species Act of 1973

· Clean Air Act Extension of 1970 (CAA)

Prior to these laws, environmental protection was largely left to the states. Following their passage, environmental regulation became the business of a joint partnership. Called federalism, the partnership divided responsibilities between federal and state governments.

The operation of the model has changed over time. Current federal-state partnerships, like most things political these days, are being reshaped by intense partisanship.

Enduring gridlock has taken Congress out of the mix. Much of the onus of climate action is being borne by presidents and state governments. It’s less than an ideal arrangement.

On the federal side of things, climate policy has become extremely unstable. It depends upon who is in the White House, their trust in climate science, and its worth to them as an election issue.

For very different reasons, Obama, Trump, and Biden agreed about the critical importance of the climate issue to their winning elections and their legacy once in office. Obama and Trump were frustrated to distraction over Congress’s inability to act and sought to dictate national policy through executive orders.

Trump’s executive actions were driven as much by his disbelief in climate science as by his disdain for the federal government and President Obama. For the 45th President, all environmental regulation at any level of government was to be erased.

A recent publication of the Brookings Institution termed Trump’s presidency a hostile takeover of the federal government. It described the hostility as involving high-priority, politically salient presidential efforts to reorient a major policy through executive initiatives where its goals depart sharply from those of key agencies and actions were taken by the prior presidential administration to realize them. (emphasis added)

Both Trump and Obama have seen the ease with which a successor can erase orders. Therein lies the instability of the federal side of the partnership equation.

If President Biden hopes to leave an enduring mark on the nation’s environment, he’ll have to seek congressional support to pass legislation that is not so easily erased every four to eight years.

The role and interests of state and local governments are not necessarily the same as those of Washington. As Anthony Moffa writes, states and localities have focused their attention on mitigation and adaptation. Individual states lack the resources and power required to fashion, implement, and enforce a national strategy.

Subnational governments are deploying a variety of laws to accomplish their pro-environmental goals. Some states, for example, direct regulators to devise rules that force utilities to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by changing their mix of generation sources — e.g., solar and wind for coal, or through greater efficiencies. Figure 1 show the environmental friendliness of each state. The darker the green shading the friendlier the state.

State and local governments decide how and for what federal block grant monies are to be distributed. At the local level, cities and counties look to meet their mitigation and adaptation goals through various measures ranging from zoning and building codes to the buildout of transportation infrastructure, e.g., installing electric vehicle charging stations and instituting bike-share programs.

States are also beginning to think in terms of regional cooperation. The Transportation and Climate Initiative (TCI) is a collaboration of 12 Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states and the District of Columbia. It seeks to improve transportation, develop the clean energy economy, and reduce carbon emissions from the transportation sector. The participating states are Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Virginia.

There is, of course, another side of this coin. Hyper-partisanship is as much in evidence at the state level as at the national. Climate consciousness has become tribal in the sense that Democrats generally accept the science behind the predicted consequences of rising temperatures, e.g., more frequent and intense storms, droughts in some areas flooding in others, the loss of species, etc. Acceptance of the science means the Democrats at all government levels are more likely to advocate decarbonization of the economy.

Republicans are generally dismissive about Earth’s warming and what it would mean should aggressive government action not be forthcoming. They are also generally supportive of the continued use of fossil fuels. As a consequence, Republican-controlled state governments look to defeat decarbonization efforts.

State governments are keeping natural gas on the front burner of their energy plans by passing legislation that preempts local governments from banning it. Such legislation has already been adopted in Arizona, Louisiana, Oklahoma, and Tennessee.

Missouri and Kansas have seen the introduction of similar legislation. In North Carolina, House Bill 220 would prohibit cities and counties from adopting ordinances to limit the expansion of (or connections to) natural gas service. Similar laws have been proposed in Texas, Florida, Georgia, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Pennsylvania, Utah, Indiana, Arkansas, Kentucky, and Mississippi.

Many local leaders say reducing the carbon and methane pollution associated with buildings, the source of 12.3 percent of US greenhouse gas emissions, is the only way to meet their 2050 zero-emission goals to curb climate change. Environmental groups agree.

According to Rachel Golden of the Sierra Club.

There’s no pathway to stabilizing the climate without phasing gas out of our homes

and buildings. It is a must-do for the climate and a livable planet.

The politics of natural gas are tricky. The issue brings labor organizations — covering various trades from pipefitters to steelworkers and plumbers — into alignment with natural gas supporters, including producers and Republicans.

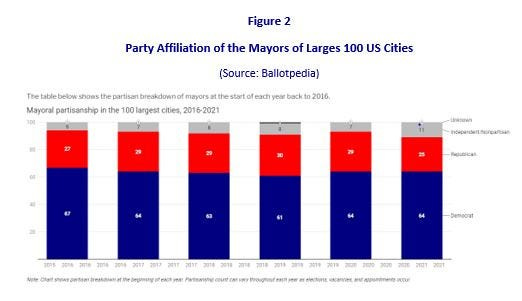

The tensions between state and local governments are part and parcel of the partisan divide. Figure 2 shows the party affiliation of the mayors of the 100 largest US cities. As of March 2021, the partisan breakdown was 64 Democrats, 25 Republicans, four independents, and seven nonpartisans.

Figure 3 identifies Republican and Democratic states just after the 2020 elections.[ii]. The red and blue states are termed trifectas by Ballotpedia. To earn the trifecta label, a state’s governor, legislature, and attorney general must all be of the same party. There are currently 38 trifecta states — 15 Democratic and 23 Republican. (Figure 3)

Although not a perfect match, the greenest states in Figure 1 correlate closely with Democratic governments and the lighter hues with the red state regimes in Figure 3. Republican and Democratic-controlled states also correlate closely with the states in Figure 4 that are the least and most likely to wear masks in defense of COVID-19.

As I’ve written before, there are strong correlations between mask-wearing in the current contagion and party affiliation. There is also a recognized relationship between a belief in science and mask-wearing.

What does this have to do with climate policy? According to a Morning Consult poll:

Climate-concerned adults are 24 points more likely always to wear a mask

in public spaces than those unconcerned with climate change.

According to the poll, climate-concerned adults (86 percent) are 14 points more likely to distance socially than climate-unconcerned respondents.

Experts say the discrepancy is due to science skepticism, personal autonomy concerns, and identity markers as opposed to following expert advice on both coronavirus and climate change. It all correlates with how Republican and Democratic law and policymakers respond to Earth’s warming.

Talk to my attorney (general)

Less than a hundred days in office and President Biden is already being sued by 21 of the 23 Republican trifecta states (See Figure 3) over his decision to suspend work on the Keystone XL pipeline. The plaintiffs in the case are Texas, Montana, Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Utah, West Virginia, and Wyoming.

The Keystone case is not the only challenge to Biden’s use of executive power. Twelve states Arkansas, Arizona, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Utah, have challenged his directive to calculate the social cost of greenhouse gases. The number is critical for federal agencies required by law to consider the costs and benefits of proposed regulations in rulemaking.

Unsurprisingly, the Trump administration barely credited the cost of greenhouse gases to society’s health, safety, and welfare. According to a recent report by Government Accountability Office (GAO),[iii] The Trump administration set the price seven times lower than the Obama administration’s estimate of $50 a ton.

The twelve states filed their suit in advance of the administration setting a price. They are alleging that the administration doesn’t have the power to set the number for something quintessentially a legislative task. A difference of opinion that I’m confident will be decided by Supreme Court.

There are other courtroom challenges to Biden’s climate plan — again, mainly by Republican trifecta states. Most of the suits will claim the administration is guilty of overreaching the authority given to the federal government by the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and other of the foundational environmental laws dating back to the Nixon era.

In fairness, Democratic trifecta states are just as litigious with Republican presidents. The Trump administration was sued hundreds of times over the course of four years. Earthjustice alone filed 200 lawsuits. Luckily for the environment, the Trump administration lost most of its court battles for failing to follow the law.

Before Trump, blue states sued the George W. Bush administration over its environmental regulations. Before Bush, red states went after the Clinton administration.

Absent bipartisan collaboration — at all levels — this insidious on-again/off-again cycle will continue. In which case, the nation will be the loser. Under any circumstance, the courtroom is hardly the place to craft climate policy.

Whether or not President Biden’s Build Back America agenda ever becomes law, state and local policymakers must be ready to act either in consort with the federal government or in lieu of it. Politics are not the only things that are local. The consequences of climate change will be felt first and most acutely at the state and local levels.

A fact that some Republican members of Congress are well aware. Representative Frances Moody, a conservative Florida Republican, believes it is well past the time for Republicans to recognize the increasing costs and dangers associated with a changing climate. Americans are experiencing these disasters firsthand, and these personal experiences are informing their views on climate change regardless of their age or party affiliation.

Informing state lawmakers of both parties, as well as climate activists, are the Climate Cabinet Education Fund (CCE) and the National Caucus of Environmental Legislators (NCEL).

More on that later.

*****************************

[i] The Act was proposed by Nixon and passed by Congress in 1974 but signed by President Gerald Ford. This 1974 law was enacted after scientists discovered widespread contamination in American tap water.

[ii] The map was done before the final vote count in Alaska. Alaska’s governor, lieutenant governor, and legislature are all Republican. Alaska’s state attorney holder is nonpartisan.

[iii] GAO is Congress’s nonpartisan investigative arm.