How to Stop the AG-onizing Resistance to US Climate Policy

In the melee that marks the 2024 election year, it is easy to lose focus on down-ballot candidates that have as much—perhaps more—influence over US climate policy as the presidential contenders. Who are these influencers? Naturally, they’re the lawyers!

But not just any lawyers. I’m speaking here of state attorneys general (AGs)—ten of whom are up for election in 2024, with an additional 30 in 2026. Whoever wins the presidency will be frustrated, and their climate-related actions will be attacked by opposition lawsuits—many of which will be led by state AGs.

Even before climate change became a critical front in the culture war, fossil-fuel-state challenges to federal climate-related actions have dramatically dragged out and down largely Democratic initiatives meant to transition the nation to a low-carbon economy. Fossil fuel states are overwhelmingly Republican, especially at the state level. To be fair, Republican AGs are only half the story. (See Figure 1)

While red-state AGs sue Democratic administrations to delay or strike down climate-related regulations responsive to the science, blue-state AGs take Republican administrations to court to stop them from unwinding protections and attempt to sue oil companies for knowingly harming human and planetary health.

Sisyphean in nature, the cycle of legal challenges has slowed the passage and implementation of laws meant to reduce the rate of Earth’s warming, as well as efforts to protect the environment and leverage private sector investment in a 21st-century power grid reliant on clean energy sources like solar and wind.

Red state challenges to largely Democratic climate-related regulations not only slow (or stop) their implementation; they often make them obsolete. A lot can change in the five or more years it takes for the court system to resolve challenges, and the long delays frequently result in agencies having to begin the lengthy rulemaking process all over again. As time is of the essence in responding to Earth’s rapid warming, the failure to regulate harmful emissions and environmental impacts in a timely manner is unconscionable.

To put “slow” into a context, consider that the 2022 US Supreme Court decision in West Virginia v. EPA was the final nail in the coffin of President Obama’s signature climate policy—the Clean Power Plan (CPP). The CPP set limits on CO2 emissions from power plants. It was first proposed as a draft regulation in 2014 and finalized in 2015.

Leading the charge against the CPP was West Virginia’s Attorney General Patrick Morrisey. The AG has led multiple assaults on the policies of both the Obama and Biden administrations.

In May, Morrisey and 24 other Republican state attorneys general launched an attack on the Biden administration’s regulatory effort to limit planet-warming power plant emissions. The proposed rule is meant to fill the void left in the wake of the CPP. In a press conference, Morrisey “promised a repeat courtroom victory against EPA and its new rule targeting emissions from existing coal-fired power plants and new gas facilities.”

Red state attacks on Democratic environmental and energy regulation are supported by a well-heeled Republican Attorneys General Association (RAGA), which receives tens of millions of dollars from fossil fuel interests. As reported by The Guardian, the association “has roped in about $5.8 million from oil and gas giants and their allied lobbying groups since Joe Biden was elected president in 2020.” RAGA has received nearly $19 million from the Concord Fund over the past decade, according to the liberal-leaning Center for Media and Democracy.

The Concord Fund is linked to Leonard Leo, the conservative Federalist Society co-chair. The society is particularly influential during Republican administrations as it serves to “vet” conservative judicial nominees. Leo and other conservative monied interests, e.g., the Koch network, are big funders of Project 2025—the conservative Heritage Foundation’s efforts to create a transition blueprint for a Trump 2.0 administration.

Although the former president has publicly disavowed Project 2025, it remains a blueprint for far-right government. Red state AGs will play the role of enablers of Project 2025 policies and the enemies of many Democratic programs, including the just transition to a low-carbon economy. The successful attack on diversity (DEI) and environment, social, and governance (ESG) initiatives in the private sectors—particularly financial and investment—owes much to Republican AGs like Ken Paxton (Texas).

Among their most recent collaborative efforts, “28 Republican attorneys general have sided with oil and gas firms to block states seeking compensation for weather disasters caused by climate change.” The cases are similar to those against tobacco companies in the 1990s, which were based on their knowing disregard for the health hazards of smoking. Blue states and cities are attempting to follow the same path—asking the courts to order oil gas companies to pay for the damages caused by harmful emissions.

Barring some a crowd-based epiphany on the part of Republican AGs and their supporters, there is only one way to respond successfully to the AG-onizing Republican resistance to science-based climate policy. Vote them out of office!

Ten states are choosing their attorneys general this November. Five of the ten—Indiana, Missouri, Montana, Utah, and West Virginia—are red. The other five—Washington, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Vermont, and Oregon—have Democrats as their legal eagles.

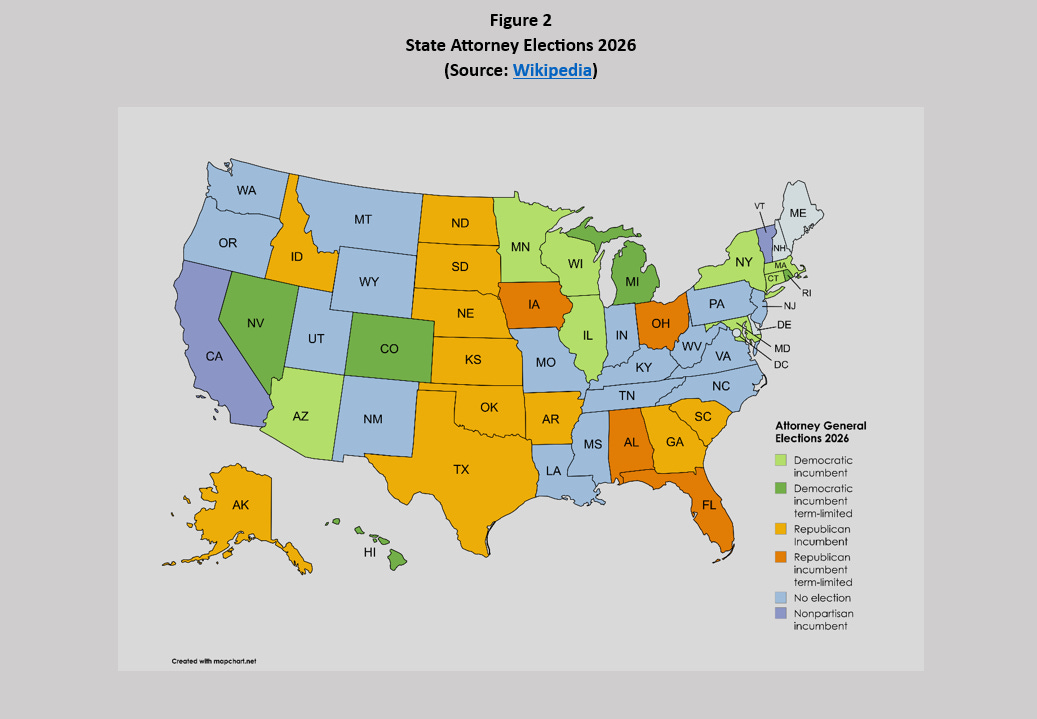

In 2026, 30 state attorneys general will be up for election. As shown in Figure 2, the partisan breakdown is 15 Democrats and 14 Republicans. The AG’s position in Vermont is considered non-partisan.

It’s good to remember that AGs are not just powerful in their own right. Often, the AG’s office is a stepping stone to bigger things. Jeff Sessions (R) became a US senator from Alabama and was appointed as Trump’s first Attorney General. Scott Pruitt went from joining with and leading legal assaults on environmental regulations to becoming Trump’s first EPA administrator—responsible for drafting and defending federal environmental policies.

AGs have moved from the courtroom to the governor’s mansion, e.g., Mike DeWine (R-OH), and become US senators, e.g., Catherine Cortez Masto (D-NV). Three AGs, including Aaron Burr, became vice president. One AG even became president; California’s former AG may soon equal Clinton’s accomplishment.

Although Harris’ victory in November would undoubtedly be a save for US climate policy, one thing is clear. The alliance between red-state AGs and monied fossil fuel interests will continue as a drag on the transition to a low-carbon economy.