A Trumped-up Clean Power Plan

As it is written, so it shall not pass!

As it is written, so it shall not pass!

Spoiler Alert: From an environmental perspective, the Trump administration’s proposed replacement for the Clean Power Plan (CPP) — dubbed the Affordable Clean Energy plan (ACE) — stinks!

That’s just the beginning of the story. A story that once again ends with climate defenders and deniers duking it out in federal court over the next two to five years.

It should come as no surprise that the Trump administration has chosen to replace its predecessor’s Plan with one that does little, if any, good for the environment. ACE reflects the high value — political and economic — the Administration places on coal and other fossil fuels and the low regard in which it holds the clean energy and efficiency sectors.

The proposed plan continues White House efforts to buck an energy market moving on its own towards natural gas and renewables like solar and wind . A movement motivated more by economics than environmental regulation. ACE, for example, makes it easier to keep dirty-old coal-fired electric plants online. As one independent — but very politic — research company wrote:

ACE is a tepid pledge to fight climate change that’s actually a coal bailout.

A less politic opinion writer might call the Administration’s proposed replacement of the Obama plan a Trumped-up CPP and just Another Coal Enterprise. Luckily for the nation, Trump’s ACE will remain in a hole never to be implemented, which may be the only positive part of this story.

Trump’s “tepid” replacement rule faces the same fate that befell Obama’s Clean Power Plan. It will be dragged to death through the courts at least until such time that one of two things happen — an environmental catastrophe of such proportion as to convince the denying-Donalds of the world there may be something to the climate change rumors; or the Democrats win back the White House.

A Democratic president could — with strokes of a pen — undo much of what Trump did to undo Obama’s environmental legacy. A legacy largely built on the exercise of unilateral executive power because of the ever-expanding partisan divide in Congress. Dueling pens have shown themselves poor substitutes for stable federal environmental and energy policies that lead and leverage the efforts of state and local governments and the private sector to create a vigorous low-carbon economy.

The courts will continue to be the venues in which climate policies are debated and decide for the foreseeable future.

Publication in the Federal Register started the clock ticking on the 60-day public comment period required by the Administrative Procedures Act. (see Figure 1) It is the start of a journey through the legal thicket that will take years to conclude — if a conclusion is even possible. A lot can and likely will happen in the intervening time, e.g., changes in administration, advances in technology, the passage of new or amended legislation, etc.

ACE, however, need not be implemented to have a destructive impact on the nation’s environment and what remains of the federal protection framework. In the litigation to come several landmark US Supreme Court (SCOTUS) decisions will be tested starting with the US Supreme Court’s 5 to 4 decision in Massachusetts vs. EPA. The case led to EPA’s endangerment finding and ultimately to the Obama administration’s drafting the CPP and other air quality regulations, e.g., methane emissions from mining and drilling operations on federal lands.

Overturning the Massachusetts decision — or those parts of it having to do with the Agency’s implied Clean Air Act (CAA) authority and responsibility to regulate greenhouse gases — would have profoundly negative repercussions regarding environmental quality and the capability of the nation to combat climate change. The case did more than establish EPA’s authority to regulate emissions not explicitly listed in the CAA, i.e., carbon. It obligated the Agency to regulate greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) should it determine them harmful to humans and a contributing cause of global warming.

The majority in Massachusetts had a much different view of the causes and consequences of global warming than EPA. The Agency defended its refusal to regulate auto emissions in part by telling the Court that the link between carbon emissions and rising temperatures “cannot be unequivocally established.” The link was termed casual.

Five justices, however, saw things differently. Stevens writing for the majority frequently mentioned the reports of the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the US’s National Climate Assessment (NCA) group. The justices were not nearly as concerned about the “uncertainty” of the science as EPA; they implied that the Agency was using it to hide behind:

Nor can EPA avoid its statutory obligation by noting the uncertainty surrounding various features of climate change and concluding that it would, therefore, be better not to regulate at this time.

If the scientific uncertainty is so profound that it precludes EPA from making a reasoned judgment as to whether greenhouse gases contribute to global warming, EPA must say so.

That EPA would prefer not to regulate greenhouse gases because of some residual uncertainty — is irrelevant. The statutory question is whether sufficient information exists to make an endangerment finding. (emphasis added)

Overturning Massachusetts could cast doubts on:

EPA’s threshold obligation to regulate GHGs not specifically listed in the CAA;

the Agency’s use of a preponderance of scientific evidence as its decisionmaking standard, i.e., for determining causes and consequences of climate change.

The majority disagreed with EPA’s interpretation of both the statutes and the science. In telling EPA to go back to the drawing board, the Massachusetts court put itself at odds with another landmark SCOTUS decision know as the Chevron deference or doctrine.

The doctrine holds where the statutory wording is clear and unambiguous the language governs. When the wording is ambiguous, however, the courts will defer to a reasonable interpretation of the meaning/purpose by the agency responsible for implementation of the act(s).

The doctrine was established in Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. and is one of the fundamental underpinnings of the modern administrative state. It has been particularly critical to the development of environmental regulations.

According to the American Bar Association, the Chevron deference has allowed Congress to paint its environmental goals in broad terms while leaving to the EPA the task of determining how best to achieve Congressional goals and objectives. There are both practical and political reasons for legislative acts to avoid the level of regulatory detail rulemaking requires. The more specific the legislation’s language, for example, the more supporters and opposers will have to argue about, and the less likely the bill will make it through Congress and onto the president’s desk.

Like many blades, Chevron cuts two ways. Deferring to EPA’s judgment in the Obama years would have a very different outcome than paying deference to Trump’s EPA. Justice Scalia believed EPA’s interpretation of both the law and the science should have been deferred to in the Massachusetts case:

There is no basis in law for the Court’s imposed limitation. EPA’s interpretation of the discretion conferred by the statutory reference to “its judgment” is not only reasonable; it is the most natural reading of the text. The Court nowhere explains why this interpretation is incorrect, let alone why it is not entitled to deference under Chevron.

A total or partial override of Massachusetts is likely to follow along Scalia’s thought train especially as Justice Gorsuch and soon-to-be justice Kavanaugh are considered his acolytes. Whether a decidedly conservative High Court will summarily throw out Massachusetts in the first challenge case that comes along depends upon whether they consider the 2007 5 to 4 decision settled law. The settled-law question is of particular interest given the unclear responses of many of Trump’s judicial nominees on such landmark cases as Roe vs. Wade and Brown vs. Board of Education.

A “settled” question of law is much less likely to be reversed suddenly in a single bound; its reversal often occurs only at the end of a stepped approach — in conformity with the Latin phrase stare decisis or to stand by things [already] decided.

A reversal of Massachusetts would leave the endangerment finding vulnerable to attack. Of all the past policy and judicial decisions that might be revisited now that CPP is out and ACE is in, the endangerment looms largest. Should the finding fall, a significant portion of the existing environmental protection framework could fall with it.

Any attempt to take down the finding comes with many risks. The endangerment finding has been the source of conflicts with the White House and its inner-circle of advisors from conservative think tanks like the Competitive Enterprise Institute (CEI) — home of one of the leading climate science deniers Marvin Ebell. Ebell speaks for many deniers — most notably Senator Jim Inhofe (R-OK) — when he says:

If you take down the building but leave the foundation, you’re going to get in trouble. We need to excavate the foundation and cart it away. The endangerment finding is the foundation.

Inhofe, renowned for having used a snowball as a prop to convince his Senate colleagues that global warming is a hoax, has been attacking the finding since it was first made in 2009. In a speech on the floor of the Senate Inhofe referred to the finding as a ticking time bomb. Inhofe correctly worried that the Obama administration would not be content just to regulate auto emissions but would apply it to electric generating plants and other industrial processes that emit CO2 and other greenhouse gases (GHGs).

Inhofe accused the Obama administration of being too clever by half by finding carbon a public danger; the Administrator is inviting lawsuits from environmental lobbies demanding that EPA regulate all carbon sources. Massachusetts and two other states have already sued in federal court…. The Oklahoma Senator is a powerful conservative voice on Capitol Hill. As the second-ranking member of the Committee on Environment and Public Works and the chairman of the Subcommittee on Transportation and Infrastructure, he is in a position to lead an attack against the finding.

Administratively rescinding the endangerment finding is no easy task. It would start with EPA’s publishing a Federal Register notice of its intent to rescind. The Agency would need to explain reasons for the rescission — scientific and procedural.

If Massachusetts vs. EPA is overturned, Trump’s SCOTUS might be willing to accept the opinion of a small and suspect community of climate-denying scientists as the basis of for EPA now reversing the endangerment call. Whether Inhofe’s snowballs would suffice as sound science, is another matter.

There are those in the Administration, like Acting EPA Administrator Wheeler, who understand how difficult it would be to withstand the onslaught of challenges that would ensue should a rescission attempt be made. Today’s climate-science is much more secure in its conclusions than a decade ago. Affirmation by a court of the prevailing scientific theories of climate change would only strengthen the hand of climate defenders in future court cases.

There is some possibility that Inhofe and other Congressional climate deniers might try to undo the endangerment finding through legislative means. Options might include amending the Clean Air Act and other environmental protection laws, prohibiting the use of federal funds for climate-science research, or limiting the jurisdictional authority of federal courts to hear cases on the endangerment finding. The legislative route would be tough to travel unless deniers were in firm control of both Congress and the White House.

Considering ACE in the larger scheme of things is critical. Although in its own right ACE falls far short of what is needed to combat global warming, Trump’s proposed replacement for the Clean Power Plan in consort with other of the Administration’s regulatory rollbacks and rescissions actively makes things worse.

On the one hand, the Administration proposes a tepid plan to reduce by 2030 CO2 emissions by at most 1.5 percent of 2005 levels. This as compared to the CPP’s reduction of 19 percent over the same period. On another hand, i.e., auto fuel efficiency standards, Trumpstefarians have proposed a rule that on a cumulative basis would increase US CO2 emissions by 321 to 931 MMt between 2022 and 2035.

The Administration’s proposed freeze of auto emission standards at 2020 levels and replacement of the CPP with its own rule were not the only announcements of negative environmental consequence in recent weeks. Also made public, although quietly, was the Administration’s declaring it no longer necessary for the nation to conserve oil — or, for that matter, energy. The oil and auto efficiency measures fit neatly together as the lower mileage standards, by the Administration’s estimate, increase oil consumption by 500,000 barrels a day.

Step back from the seeming climate policy chaos created by the Administration, and you’ll see an integrated series — intentional or not — of executive actions that feed off each other creating a formidable battle line between climate deniers and defenders.

The best defense of the nation’s need for aggressive national climate protections is to prevail in the court of public opinion. To have any real hope of success in convincing voters to support the candidacies of climate defenders arguments against ACE and other of the Administration’s de-regulation proposals, defenders will need to connect the dots.

A Morning Consult/Politico survey of a national sample of 1,964 registered voters shows that 48 percent of the population either somewhat or strongly supports the Environmental Protection Agency’s proposed Affordable Clean Energy rule. Digging a bit deeper into the survey results it appears that isolated questions led to offsetting answers.

When respondents were told that the proposed rule would reduce 2030 emissions by as much as 1.5 percent, 45 percent looked favorably on Trump’s plan, while one-quarter were either unsure or had no opinion. (Figure 2)

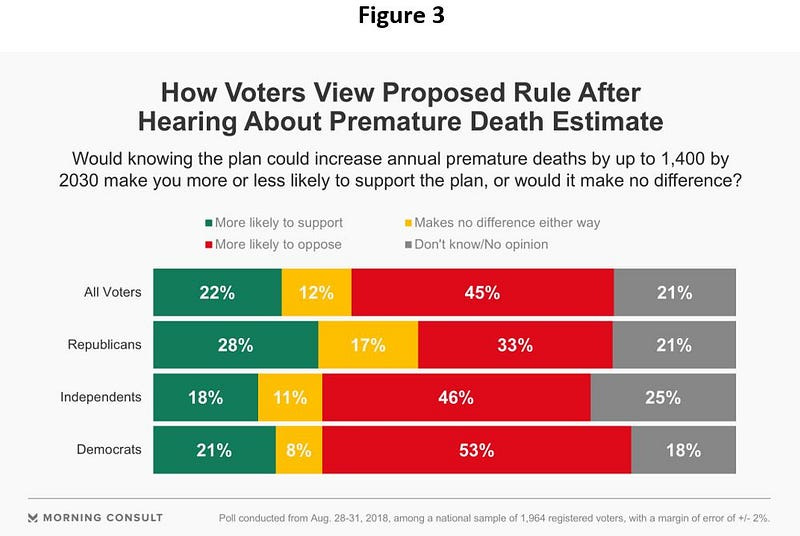

When told that ACE would result in up to 1,400 annual premature deaths from inhaling particulate matter these same respondents indicated they could be convinced to oppose the plan. (Figure 3)

The moral of this story is the importance of putting ACE and any other of Trump and company’s actions within a proper and larger context.

It is a mistake to believe that EPA’s authority and obligation to regulate greenhouse gases is settled law. In Trumpworld nothing is settled until it is. Climate cases like Massachusetts were often decided by the thinnest of majorities. By the time ACE and other Trumpian edicts find their way to the US Supreme Court, the judiciary’s tip towards conservatism will have already occurred. Whether the newbies on SCOTUS will feel compelled to stick with earlier decisions is yet to be known.

The best way to guard against the weakening the body of environmental law that has come before?

Convince voters and their representatives that Trump and his coal-cronies are more interested in buying time to continue pumping their pollutants into the nation’s air and waterways than in preserving Earth’s declining resources for future generations — or even the current generation of coal workers who have lost their jobs because of competition with natural gas and renewables like wind and solar.

Encourage political leaders to finally put in place legislated science-based solutions to combat climate change and build resilient communities.

*****

Note additional sources of information on ACE

Civil Notion’s one-page ACE fact sheet is available here.

EPA Fact sheets, the preamble, and the proposed rule, and the Regulatory Impact Analysis are available here.

EPA’s analysis of ACE’s costs and benefits is here.

Lead image: captured from You