911, What’s Your Climate Emergency?

Our next President should declare a national emergency on day 1 to address the existential threat to all life on the planet posed by…

Our next President should declare a national emergency on day 1 to address the existential threat to all life on the planet posed by Climate Change.

Representative Ilhan Omar (D-MN)

By declaring a national emergency concerning the southern border of the US, Trump may have unwittingly given the next Democratic president an ad-ditional weapon with which to combat climate change. Although previous presidents have declared national emergencies for things like swine flu and preventing business with people or organizations involved in global conflicts or the drug trade, none have sought to use their executive power in quite the same manner as Trump has done with his immigration declaration.

Oddly, both Republicans and Democrats opposed the emergency declaration using much the same language. Democrats like House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) and Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) were quick to argue that the dec-laration was an attempt to circumvent Congress — but suggested that a future Democratic president could use the same trick for a different emergency, i.e., climate change or gun control. To emphasize the point, Senator Sanders made a presidential declaration of a national climate emergency an integral part of his recently released climate defense plan.

Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL) agreed with Pelosi and Sanders that Trump’s emergency declaration could be cited by future Democratic presidents as the authority needed to declare a national climate emergency. Rubio warned in an interview with CNBC that:

We have to be careful about endorsing broad uses of executive power. If today the national emergency is border security…tomorrow the national emergency might be climate change.

A situation Rubio would prefer not to happen.

What makes the legal questions surrounding Trump’s emergency declaration so intriguing is that new fields are being plowed. An unknown that will come to take on meaning starting with this case is what constitutes an “emer-gency?” Since the 1976 National Emergencies Act offers no specific definition of the term national emergency, the defining task falls to the judiciary.

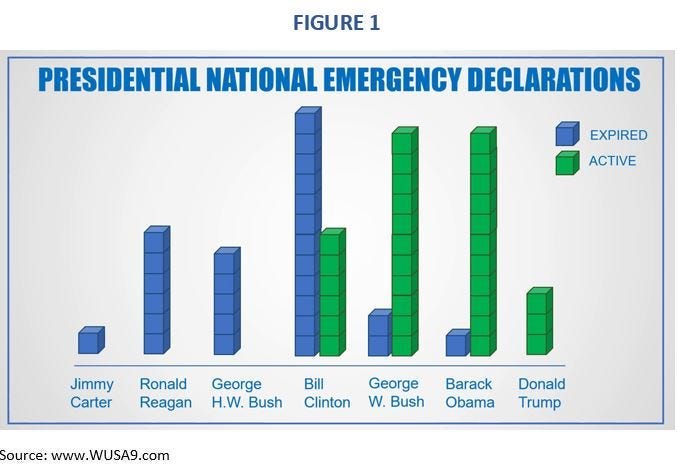

As stated earlier, emergency declarations have had mostly to do with san-ctions, i.e., separating bad people and nations from their ill-gotten gains, e.g., through terrorism, smuggling, and violations of human rights laws. Since the National Emergencies Act came into effect in 1976, there have been 59 national emergencies declared. Of the 59, 45 were sanctions; the remaining 12 involved public health (1), the continuation of export control regulations (7), and a legal issue (1). Two declarations were military in nature; one was issued at the time of the September 11th attacks. The second declared military emergency was Trump’s February 15, 2019, Proclamation 9844 having to do with the southern border wall.

Figure 1 shows the number of national emergency declarations by president starting with Jimmy Carter. Note that of the 59 emergency declarations issued, 31 are still in force.

What distinguishes Trump’s February 15th declaration from the other 58 is his using it to justify taking funds appropriated by Congress for one purpose and using them for another — construction of his proposed border wall. The 2019 Appropriations Act passed by Congress explicitly rejected Trump’s $5.7 billion demand for a border wall and forbade construction in certain areas, including carve-outs for wildlife areas.

The Sierra Club, along with the Southern Border Communities Coalition, have challenged Trump’s emergency powers declaration in federal court. The lawsuit, Sierra Club et al. v. Trump argues that:

…the president’s declaration and diversion of funds violate core constitutional principles and multiple laws and statutes, including the 2019 Appropriations Act, the Constitution’s Presentment Clause, and the constitutional principle of separation of powers.

The claim having to do with the Presentment Clause rests on Trump’s having signed the 2019 Appropriations Act and then rejecting it by declaring a national emergency.

Like many of Trump’s assumptions about the power of the presidency, his believing he can circumvent the US Constitution’s separation of powers clause by declaring something a national emergency is mostly wishful thinking. I would hasten to add that Democratic thinking in this instance seems equally fanciful.

A national emergency declaration conjures up images of enemy hoards at the gates and the need for swift marshal action by the president — man the parapets, the Constitution be damned! An emergency declaration itself, however, is little more than a routine executive order, memorandum, or proclamation[i] and cannot circumvent applicable laws and regulations.

An emergency declaration, however, is not without special meaning. The declaration triggers emergency clauses in various laws — generally allowing an executive branch official to do something they might not ordinarily be able to do outside of the order but still inside the law.

For example, when President Obama declared a national emergency because of the 2009 swine flu outbreak, he also declared:

…that the Secretary [of Health and Human Services] may exercise the authority under section 1135 of the SSA [Social Security Act] to temporarily waive or modify certain requirements of the Medicare, Medicaid, and State Children’s Health Insurance programs and of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Privacy Rule throughout the duration of the public health emergency declared in response to the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic.

It’s imperative to understand that a president’s emergency power is defined not by the declaration but by the emergency clauses in the applicable statutes.

The Brennan Center for Justice has compiled a list of more than 130 statutes that a president can trigger with an emergency declaration. Although a few of the statutes would be useful in the fight against climate change, none of them are of adequate scope to serve as the foundation for an integrated national climate defense plan.

Below are several examples of statutes that might be called upon under a national climate emergency declaration:

· Oil leases are required to have clauses allowing them to be suspended during national emergencies. [[ii]] If climate change is a national emergency caused by fossil fuels, then suspension seems like a logical response.

· The President has emergency powers to respond to industrial shortfalls in national emergencies. [[iii]] This could be used to support the expansion of battery or electric vehicle production. Another provision allows the President to extend loan guarantees to critical industries during national emergencies. [[iv]] This could be used to support renewable energy more generally.

· The Secretary of Transportation has broad power to “coordinate transportation” during national emergencies. [[v]] This might allow various restrictions on automobile and truck used to decrease emissions of greenhouse gases.

Following a decision by the 9th US Circuit Court of Appeals that prevented the administration’s beginning construction on the border wall, the administration sought the involvement of the Supreme Court.

The High Court gave the Trump administration a temporary green light to begin work paid for with military funds Congress had earlier denied. The order is temporary and limited to already existing portions of the wall.

The Supreme Court’s decision temporarily letting the Government use the identified funds for fence repairs is not presumptive of what the final decision in the case will be. However, it doesn’t bode particularly well for the plaintiffs — not only in Sierra Club but in other cases as well, e.g., Center for Biodiversity, et al. v. Donald J. Trump, et al.

In the High Court’s own words, it stayed the lower court’s permanent injunction because the Government has made a sufficient showing at this stage that the plaintiffs have no cause of action to obtain review of the Acting Secretary’s compliance with Section 8005. It is hard to handicap the Supreme Court.

However — I think the Court would have been inclined to take the compromise position Justice Beyer laid out in his separate middle-ground opinion. As Beyer indicated, the Government could have signed the contracts with the start of construction contingent on the High Court’s decision in the case.

From a strategic point of view, there are two questions addressed:

· Should an emergency climate change declaration be a Democratic priority?

· Should support for an emergency declaration be a requirement for endorsement of a candidate?

I think the answer to both questions is “optional.” In my view, support for an emergency declaration is more useful in some situations than in others.

The phrase emergency declaration will spark the attention of both the media and voters. The words are active — conveying both the urgency and immediacy of the problem and suggesting an action that could help to keep the world on the right side of the 1.5 degree Celsius threshold. The call for a climate emergency declaration is being used successfully by groups as an organizing tool. Eighteen countries and over 900 hundred local jurisdictions, e.g., cities and counties, have already declared a climate emergency.

Moreover, organizations like the Extinction Rebellion, Climate Emergency UK, and The Climate Mobilization in the US are actively organizing and have made available advocacy resources, e.g., draft pledges of support for a declaration, background information on warming and organizing tips.

To the litmus test question, I would say if used at all in determining whether a candidate is endorsement-worthy, it should be just one of many factors to be considered. In the grand scheme of things, there are more critical issue criteria on which a candidate should be judged, e.g., positions on environmental justice and re-forestation.

*************************

[i] Presidents have historically exercised their authority through several written instruments — executive orders, memoranda, and proclamations. There is no hierarchy between these written instruments. The primary difference between them is an executive order must be numbered and printed in the Federal Register.

[ii] 43 USC 1341

[iii] 50 USC 4533

[iv] 50 USC 4531

[v] 49 U.S.C 114

Lead photo: Kristin Mority on Unsplash